Courtesy of the Fisher Heart at Bard School

The Summerscape Pageant at Bard School is at all times a spotlight of midsummer. Leon Botstein, president of Bard and director of the American Symphony Orchestra—a company with a particular style for beneficial however obscure repertory—chooses annually a composer whose character, and that of his mental circle, are worthy of exploration after which, a bit perversely, picks an uncommon grand opera by not that composer however a type of related to his motion, and levels it within the Frank Gehry-designed Sosnoff Theater of Bard’s splendid Hudson River campus.

This yr, the composer on the heart of the pageant is Bohuslav Martinů, a Czech modernist who left dwelling for Paris in 1923 (what composer didn’t run away to Paris then, if they might?) and later, when battle threatened the Parisian scene, on to the USA. His later years had been divided amongst his three international locations, and he remained, although by no means a preferred style, prolific and revered till his demise in 1959. There shall be conferences in August round Martinů and the actions he associated to, climaxing with a live performance presentation of Julieta, his surreal opera of 1936.

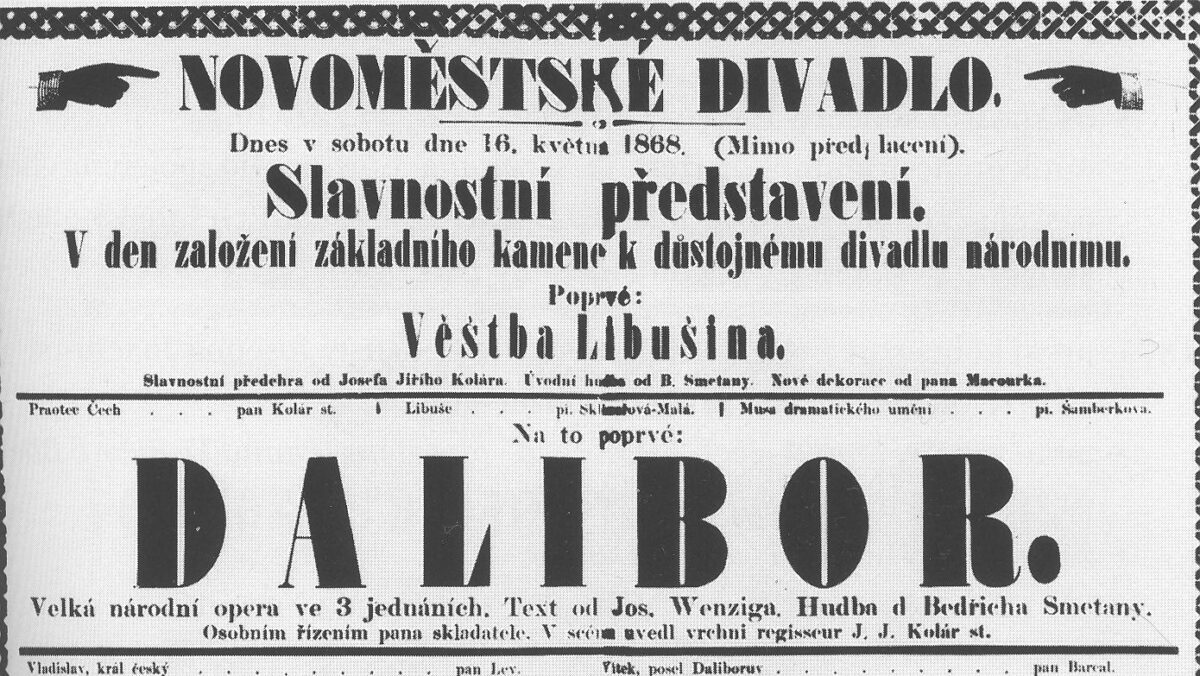

However meaning the centerpiece of the pageant should be the work of some associated composer, and Botstein’s choice, curiously, is his compatriot Bedṙich Smetana’s Dalibor, which had its premiere in Prague in 1868, failed, was revised a bit, however didn’t enter the favored repertory—and solely within the kingdom of Bohemia—till after the composer’s demise.

“It’s tough to seek out an opera that matches the custom of the Pageant,” Botstein defined to me. “A piece little recognized however worthy, with the total grand opera equipment.” He has offered different Czech works—Janácek’s Osud and Dvorák’s Dmitry—and so they too required full choruses and a big orchestra. “You possibly can’t threat a purely educational work,” he muses. “Theatricality is vital. Dalibor has the rescue plot, the patriot imprisoned, the lady who disguises herself as a person to get him out—individuals who know Fidelio are a step in direction of understanding what’s going on.”

Bedrich Smetana

Dalibor marks a conjunction of two widespread forms of opera: the rescue opera—an eighteenth-century standby—and the opera of nationalistic fable, one thing like a theatrical anthem, that got here into trend within the age following the French Revolution. For the Czechs, who had been establishing themselves after centuries of German cultural colonialism, the intrinsically musical character of Czech tradition referred to as for celebration and works within the nationwide register.

The rescue trope had a protracted custom. You can say it was invented by Euripides with Helen in Egypt and Iphigenia in Taurus, in each of which Greek princesses are rescued from barbarian kings within the nick of time. The strain of risk and escape was a present to playwrights and composers, to not point out actors.

Suspenseful Iphigenia impressed dozens of operas; thirty composers set the story, Gluck, practically the final, being essentially the most well-known. Dalibor is uncommon in that it raises our expectations of escape after which doesn’t give it to us. The hero’s patriotic frustration might have one thing to do with Smetana’s hopes for the revival of Bohemia, which was going by a rebirth at the moment.

Smetana was born close to Prague in 1828 and have become a virtuoso pianist, although it was a very long time earlier than his potential as a composer manifested. In the meantime, he accepted a conducting put up in Sweden, the place the chilly local weather killed his spouse and piano companion. When he returned to Prague, it was to a vigorous controversy in that multi-ethnic metropolis over whether or not theater (and opera) must be given in German or in Czech, and whether or not native Czech composers or Italians in translation ought to make up the operatic repertory. Related linguistic disputes had been happening at the moment in Norway, Eire, Croatia, Catalonia and Ukraine, however the Czechs centered on the musical message.

After the Revolutionary period, the favored viewers (and opera was a preferred artwork kind) ceased to care about legendary heroes and have become extra all for nationwide figures inspiring nationwide occasions. When you couldn’t cheer to your oppressed nation within the streets or within the press, you might cheer for it on stage and hum tunes within the native dance rhythms. In Bohemia that meant the polka. Smetana stuffed his operas with polkas, although he didn’t borrow people tunes however invented them himself.

In Prague, German had lengthy been the language of the elite, and subsequently of opera. (In Mozart’s day, there had additionally been a courtroom opera that, just like the courtroom opera in Vienna, sang in Italian.) Smetana joined the agitation for a nationwide opera and hoped for a place as its conductor, although the few Czech works out there tended to be of an unsophisticated ballad-opera selection. Finally a “Provisional Theater,” performing operas in Czech, opened in 1862, and although its conductor most well-liked translating Rossini and Verdi, Smetana was in a position to safe a fee for his first stage work, Brandenburgers in Bohemia, a gentle success within the type of Meyerbeer.

In 1866, he produced Prodana Nevesta, The Bartered Bride, his biggest triumph. Mockingly, this comedy, although full of polkas within the rural Bohemian method, was not supposed to be the nationwide opera—its vigorous antics lack the grandeur Smetana felt was referred to as for. And but Bartered Bride and his tone poem, Ma Vlast (or no less than The Moldau), grew to become his most beloved works, the emblems of Czech tradition world wide.

Bartered Bride owed its success, partially, to its lightness. To translate a comic book opera to get laughs was not seen as violating nationwide sanctity. Just like the comedian operas of Mozart, Rossini, Donizetti and Offenbach, Bride might be carried out in any handy native tongue.

Like Smetana, his most well-liked librettist, Josef Wenzig, was a German-speaking Czech who most well-liked to put in writing verses in German. The 2 operas he wrote for Smetana, Dalibor and Libuse, had been painstakingly reworked into Czech verse by the poet Ervin Spindler, with word-choices that made it doable to sing the identical music in both language. Singers have discovered the Czech stresses and word-choices awkward—they arrive throughout as “libretto-ese” to Czechs conversant in the later operas of Dvorak, Fibich and Janacek. This was a problem in Prague when the audio system of German and people of Czech had been contending for nationwide symbolism.

However this was not Wenzig’s solely downside. He lacked the present for dramatic energy, for constructing a scene right into a theatrical motion. There are few moments in Dalibor that wake you up, make you longing for the subsequent encounter. The characters sing collectively however don’t confront one another. The richness of Dalibor’s melodies doesn’t broaden into sweeping, swift-moving scenes.

However the theme of the noble-minded prisoner fits a nationwide message. The opera opens with a trial scene—trials make nice theater, civic rituals that an viewers can perceive. A sure Milada seems on the courtroom of King Vladislas to demand the demise of Dalibor for slaying her brother, a royal official, and Vladislas responds with a protection of feudal legislation and order. (Because the Czechs remembered, if nobody else does, Vladislas was a overseas, Polish prince elected to the Bohemian throne.)

Then Dalibor enters to defend himself—he was avenging his beloved buddy, the musician Zdenek—and he sings so nobly that Milada falls in love on the spot, although she and Dalibor have by no means met. She then disguises herself as a boy and will get a job with Benes, Dalibor’s jailkeeper—simply as in Fidelio.

We’re on tenterhooks for the subsequent scene or two—will the jailor give Dalibor the violin he has requested for, and can the disguised Milada be capable of use that excuse to get in to see him, declare her love and plan an escape? We all know the reply, however there may be dramatic pressure (and a few very fairly tunes) whereas we watch it unfold. Additionally there may be the ghostly visitation (a violin solo) from Dalibor’s beloved Zdenek to cheer him up.

In Prague, by the way in which, Zdenek’s Violin is usually stated to be a nickname for a medieval engine of torture utilized to the shoulders. Supposedly, a prisoner confined in what’s now referred to as Dalibor’s Tower sang to the violin—or howled in agony—and his cries, heard by passers-by (who tossed him their spare change), had been referred to as “the track of Dalibor.”

Particulars of the folks story are imprecise, however within the opera, the violin turns into an precise musical instrument, performed from the subsequent world by the spirit of Zdenek. From the agonized cries of a condemned prisoner to the amorous despairs of a lonely tenor will not be a lot of a leap for an opera story. In the meantime, Milada, disguised however permitted a quick love duet with the prisoner, makes use of an precise violin to assuage the jailors into letting her go to him. Dalibor is meant to play this to summon assist for his jailbreak—besides {that a} string breaks on the climactic second, which Dalibor appropriately interprets as a foul omen. Everyone dies, interrupted by enticing chorales. King Vladislas will get one other good-looking aria, maybe as a result of Smetana was courting the favor of Franz Josef, the king’s direct descendant.

Dalibor was not successful at its first listening to, in 1868. For one factor, at a time when nationwide faculties had been in battle, many a neighborhood patriot thought Smetana’s through-composed melodies, gliding into each other with little break, savored of the hifalutin type of Richard Wagner. Wagner was actually on the forefront of recent music within the 1860s, and his affect on such Bohemian-born composers as Dvorak and Mahler is indeniable, however he was totally, passionately German. All this interfered with the acceptance of Dalibor as a nationwide image.

Conductor Leon Botstein (Ric Kallaher)

Smetana, who grew to become deaf within the 1870s after which mad within the ‘80s, didn’t dwell to see this work turn out to be widespread. However from its first revival in 1886, two years after the composer’s demise, Dalibor entered the Bohemian repertory, reaching its 300th Prague efficiency by 1914. In the meantime Smetana had composed the even statelier Libuse, on an much more static Wenzig libretto, from the legend of the pagan prophetess who based Prague and its first reigning home.

“Dalibor has an uncommon efficiency historical past,” Botstein advised me, explaining its choice. “Mahler gave the primary Vienna efficiency,” in German in 1897. The opera was then translated into many Slavic languages, however grew to become a favourite solely at dwelling. “I thought-about staging Libuse, however Dalibor is much less crudely nationalistic. Too, the opera is through-composed—no spoken dialogue. And it grew to become a preferred favourite among the many Czech-speaking viewers, regardless of Smetana’s poor command of Czech. Communist Czechoslovakia preferred him too, and so they weren’t nice admirers of Dvorak or Martinů. Smetana was admired for his craft by Heinrich Schenker, the theorist and critic in Vienna within the early twentieth century, who thought-about himself a classicist and was rabidly anti-Mahler.” So Dalibor was a favourite with each Mahler and his nemesis.

Dalibor shall be given 5 performances between July 25 and August 3 on the Sosnoff Theater, totally staged by Jean-Romain Vesperini, who staged Saint-Saens’s Henry VIII there in 2023, carried out by the American Symphony Orchestra performed by Leon Botstein.